What did Kuyper and Nietzsche discuss during their meeting in a mountain hut on the flanks of the Diavolezza, the Devil’s Mountain, in 1882? And how did their experiences translate into their thinking? Share in Kuyper’s adventures in the European Alps — and those of his silent companion, Zarathustra. What did they see unfolding before their very eyes in the eternal snow?

First Fritz. As is often emphasized in biographies, Switzerland played a crucial role in Friedrich Nietzsche’s development.[1] There are books about his life in Switzerland — not only in the Alps but also about his ten formative years, from 1869 to 1879, as professor of classical philology in Basel (Hoffmann 1994; especially Janz 1994). This article concerns the eight summers between 1879 and 1888 — out of a total of nine — that he spent on the Engadin plateau in eastern Switzerland, his arcadia. From 1881 onwards, the village of Sils-Maria, in Nietzsche’s eyes, was “a kind of end of the world” (Lütkehaus 2015, 21).

Here he wrote, among other works, his pivotal philosophical allegory Thus Spoke Zarathustra, completed in 1884, well known for its Übermensch or “Superhuman.” “The birthplace of my Zarathustra,” he called it: “Beginning of August 1881 in Sils-Maria, 6,000 feet above the sea, and at a much higher altitude above all human affairs.”[2] Here he made mountain hikes that left their mark on his work. Although he usually hiked long days around Lake Silvaplana, Nietzsche never became a serious mountaineer, nor did his health — and bad eyes — permit it (Lütkehaus 2015).

It was here during an 1881 hike at the base of a large boulder that his idea of “eternal return” was born, which he himself called the central idea of his life as a thinker. A memorial stands today at its presumed site, the “Zarathustra stone” (Lütkehaus 2015, 65). Here he rented a room in a house that today is called the “Nietzsche-Haus,” which welcomes tourists and serves as a study centre for his work. For Nietzsche, then, Switzerland was not so much the birthplace of tragedy as of his life’s purpose.

Then Bram. On the death of the Dutch former prime minister in November 1920, The Guardian published the usual “obituary,” a life sketch of the deceased. It’s a fairly accurate one-column, provided by Reuters news agency in The Hague. And then suddenly a phrase jumps out that makes one sit up and take notice: “He was one of the leading Alpinists of his day” (The Guardian 1920).

This is not exactly the image of the man we’ve had since. His travels yes, they are well known, such as his American tour in the fall of 1898 and the nine months after his premiership, in 1905 and 1906, that he travelled “around the Old-World Sea” — as he himself described his greatest adventure, visiting and recounting everything he encountered in the triangle between Odessa, Khartoum, and Tangier (Kuyper 1907, v). Besides, we know him as a somewhat pudgy, stocky man, at home in a study, but not exactly the mountaineering type.

A Different Person in the Mountains

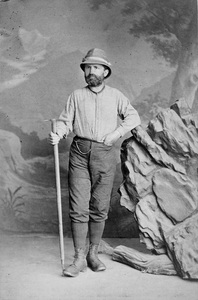

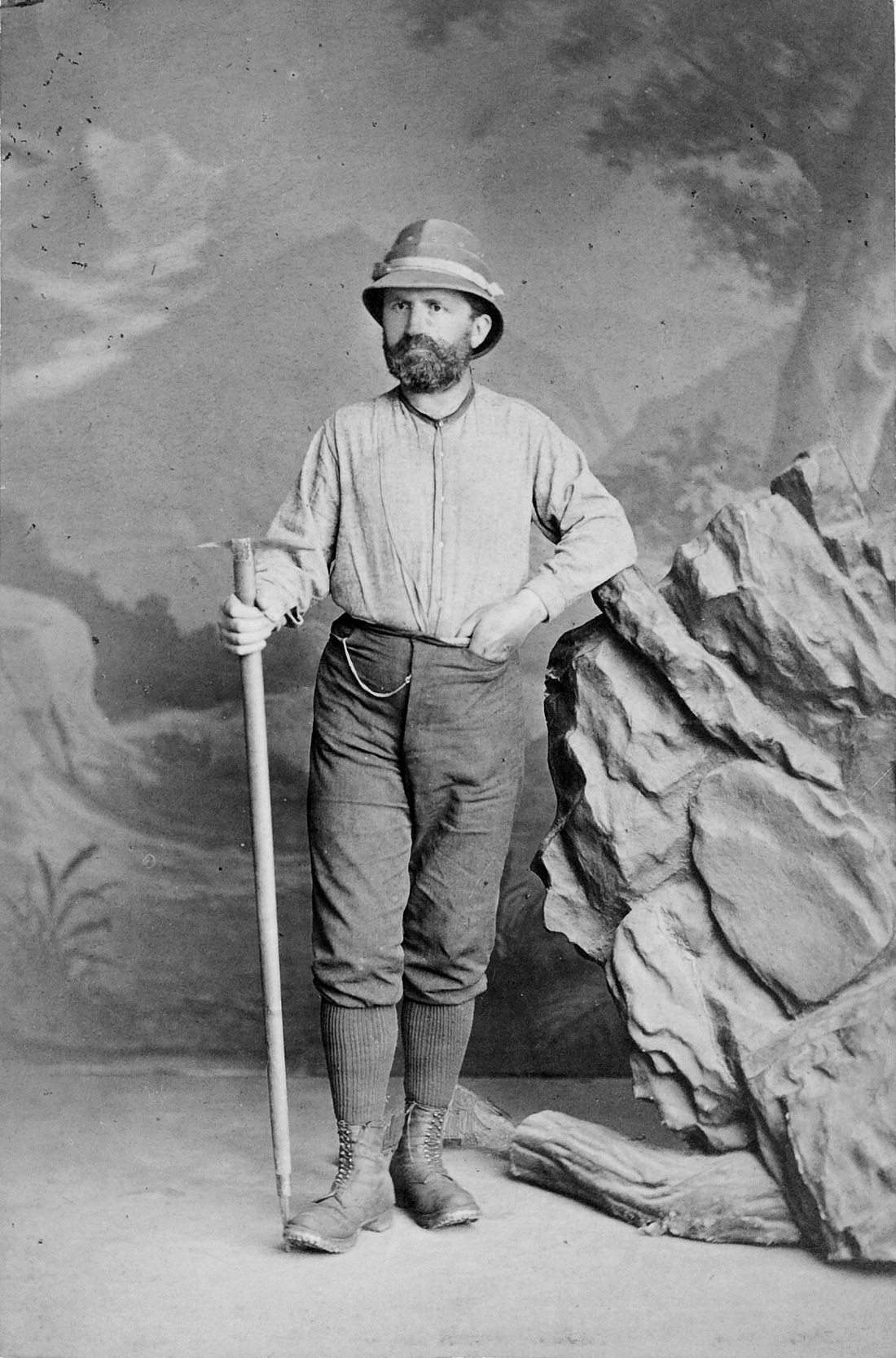

However, there are two photographs that reveal a different side of Kuyper. The first one shows a man in his thirties with a beard, in mountain attire, posing next to a boulder in a Swiss photo studio: a “sportsman” as it was called in those days. It is a man whom you can imagine lifting his eight children all at once: two in his arms, two on his shoulders, two on his legs, and two hanging around his neck front and back. Kuyper stood less than 5.5 feet (1.67 meters), quite short even for his day, but did calisthenics his entire life and loved to boast of his fitness.

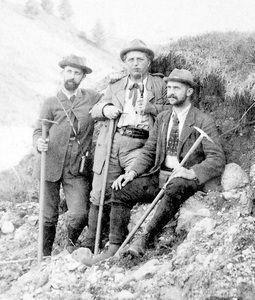

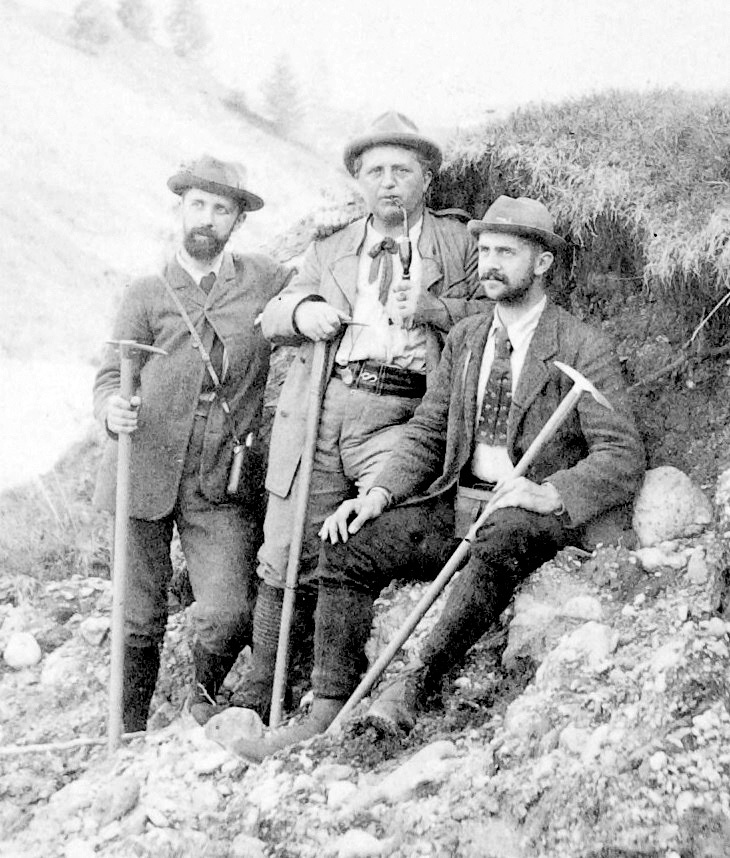

The other photograph shows a middle-aged man, dressed in a Tyrolean suit, pipe in hand, quietly waiting for the photographer, standing between his sons Herman and Abraham Jr., also in some kind of mountain gear.

The photographs have been published often; the story behind them will be told here for the first time. There were rarely any eyewitnesses, and in his public life his mountaineering was almost never mentioned. In the lofty mountains, apart from guides and a stray fellow mountaineer, he was mostly all alone, about which he would sometimes honestly complain in his letters.

He once recounted how it all began. Overworked as a young member of parliament in 1876, he spent a winter on the Mediterranean and a summer in Switzerland. He had his family come over; the sixth child, daughter Cato, was born in Nice. In the spring, they moved to the village of Sils-Maria on the Engadin plateau — the very same village where Nietzsche would stay a few years later.

One day a long walk changed his life. For the first time in many months his poor head relaxed a bit and he was able to sleep well. Kuyper would not be Kuyper if he had not seized upon this discovery resolutely. Sporadically preserved letters to his family back at home, from the following years, show that he had discovered the mountains.[3]

Furthermore, he occasionally let something slip in his interviews. In December 1901, the new Dutch prime minister was questioned at length by a journalist from the Neues Wiener Journal. Well, he was no stranger to Austria; in recent decades he had gotten to know the country on mountain tours. As an Alpinist he had conquered, among other things, the Ortler in South Tyrol, the highest mountain in the Dual Monarchy (Hercovici 1901). He also stated to the Neue Freie Presse — another Vienna newspaper — the following year that he still enjoyed hiking in the Austrian mountains, his age permitting (Kuyper was almost 65) (Neue Freie Presse 1902).

Fortunately, we have one eyewitness account. In an 1897 family newspaper, daughter-in-law Marie Heyblom shared more about it (Kuyper-Heyblom 1897). Whoever has not experienced Kuyper in the mountains, she maintains, does not know him. No more cheerful and jovial fellow traveller than he, relieved of all his cares and worries. Once strapped into mountain clothes and with a rope on his back, he is a different person. He prefers to undertake tours all on his own, but when he travels with companions, he drags them to the tables of every hotel they meet along the way and orders wine to be served.

He ignores the chic hotel guests who glare at their smelly clothes, and along the way he shares all his Alpine experiences to his heart’s content, any other subject being taboo. His enjoyment increases even more when they ascend a glacier wall and the tour takes them over snow and ice. He points out the wonders of the glacier world, and once arrived at a mountain hut he provides warm broth. He loves outpacing the guides but prefers even more to trek the mountains alone for weeks at a time.

Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory

The account makes a distinction between two types of tours. Usually Kuyper undertook treks that took him alone through all the Alpine countries. But sometimes he also ventured on expensive hochtouren, climbs at high altitude, always with two guides and often in the company of other climbers. Those climbing tours sometimes led to summits that could not be reached on foot alone, but most of them were accessed by ascending across the glaciers. It was on these hochtouren that Kuyper’s Alpinism was most evident.

The rest of the story can be found only in letters to his family insofar as they are extant — most years are missing. There is enough to know that Kuyper was modest when he listed his adventures in a note in 1912. To his list of Switzerland, Tyrol, the Pyrenees, Norway, and America can be added at least the French Mont Blanc massif, in Italy both the Alps and the Dolomites, and also the Tatra Mountains in the Hungarian part of the Dual Monarchy, now Slovakia.[4]

Take as an example the summer of 1886, the year of the Doleantie. What we know is where he stayed for a fortnight in August, that is, two of the six or seven weeks he spent each summer in the Alps. The first of these two weeks was already filled with wonders. From South Tyrol and the Italian Dolomites, he travelled back to Switzerland by train via Milan. We know that his tours ended in Geneva, from where he took the train to Paris, where he had arranged to meet Jo.[5]

After spending Sunday, August 8 in the small mountain village of Sulden in South Tyrol – South Tyrol being Kuyper’s favorite place on earth — his tour started the ascent on Monday, August 9, to the summit of the Ortler, Austria’s highest mountain at 12,800 feet, almost 4,000 meters. In fact, the Ortler was only conquered in the nineteenth century. Summits like this involved actual climbing; not every section could be reached on foot.

The next day, the group entered Italy over the high-altitude glacier of the Eissee Pass. That same day they also climbed Monte Cevedale at 12,400 feet (3,800 meters). From Wednesday they continued to Santa Caterina di Valfurva, Ponte di Legno, and Pinzolo. Apparently, the weather became too bad for further climbs. On Saturday, Kuyper travelled to Göschenen in Switzerland, by train through the Gotthard Tunnel that had opened four years earlier. That Sunday he wrote home that he had enjoyed it immensely. “Climbing the Ortler Peak and traversing the Eissee Pass were magnificent experiences, Jo dear.”[6]

In Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory, American literary scholar Marjorie Hope Nicolson outlines a small cultural history of our changing experience of mountains. She traces the signs of that shift in literature and science, which occurred even before Romanticism. How had the representation of high mountains as places of doom and darkness, as late as the eighteenth century, shifted to that of the infinite and the sublime? Not only poets expressed it; so did theologians and natural scientists (Nicolson 1997).

From a world in chaos to the highest happiness, from “Gloom” to “Glory” — the new experience of lofty mountains would, also literally, peak in Romanticism. Many peaks, like the Ortler, were not climbed for the first time until the nineteenth century. That had little to do with technical developments — it remained a battle of man against mountain — and everything with the new perception of mountains. Willingly yet also unknowingly, Kuyper was part of it; he was more of a romantic than he ever admitted to himself.

The classic articulation of this experience of the sublime in the high mountains comes from Edmund Burke. In his A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, he knew as early as 1757 how to put it into words. Quite possibly, Kuyper had read them. In 1873 he stayed in bed to fight the flu and bravely worked his way through Burke’s Collected Works, the latter with great pleasure.[7]

But he could, after all, draw on his own experiences of the sublime; the images came to him effortlessly, especially when he was writing his Sunday morning meditations. Take the image of the sunset that could make snow blaze, or that of the Norwegian sky that he had seen colored deep red: “and above all, a setting sun that sometimes makes the snow-white peaks of the Alps glow, or also the Northern Lights that know how to dye the firmament red with a red that does not cover but opens up solemn depth.”[8]

Grasping the Abyss with Eagle’s Talons

His very last letter was dated Saturday evening, August 5, 1899, at six o’clock, written in the casino town of Luchon in the French Pyrenees, where he was taking a cure — his last letter to his dear Jo, that’s to say, who unbeknownst to him had around the same time met with an accident on the Morteratsch Glacier near Sils-Maria.

Kuyper wrote that he himself had taken the tour over that glacier to the viewpoint of the Diavolezza — nearly 10,000 feet or 3,000 meters — seven times. “She is beautiful,” he added. Jo should, too.[9] And Jo did. At least, she had also by that time been walking on glaciers for years, as had her eldest sons and – perhaps most frequently of all – her three daughters. What is certain is that she fell on the Morteratsch Glacier and suffered a hand injury. What is also certain is that she was subsequently nursed in the Grimsel Hospitz in the Bernese Oberland, contracted typhoid fever and died of it, aged 57.[10]

Nietzsche also made the trip to the Diavolezza, the Devil’s Mountain, which is the main vantage point near Sils-Maria. From 1879 onwards, Fritz and Bram spent five summers in the Alps together, for a total of about eight months. Often they were both on the Engadin plateau and made the same treks. Inevitably they ran into each other somewhere. One day in early August 1882, Nietzsche’s third summer in the Alps and Kuyper’s sixth, they both arrived at a Sennhütte, a mountain hut, at the end of a rainy afternoon. Of course they had a chat: about that day’s particularly bad weather. About what else? For Kuyper didn’t really read anything by Nietzsche until the summer his youngest son Willy died, while Daddy was far away in the Alps and could not be found for days. This was in early August 1892, ten years later and a year after the publication of the final part of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. That summer he read the book and read it during his stay in the Alps — a remarkable fact!

In the Netherlands, Kuyper was virtually the first to draw attention to Friedrich Nietzsche. Kuyper at once introduced him to a wider audience. In his rectoral address of 1892, “The Blurring of the Boundaries,” he portrayed Nietzsche as a new Multatuli, the Dutch rebel against convention: posessing a sublime style, and content-wise a representative of a unique zeitgeist.[11]

For eight summers in the Swiss Alps, Nietzsche worked on books like Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Like Kuyper and unlike Nietzsche himself, Zarathustra wanders from Alpine peak to Alpine peak. Not only does he climb higher and higher, he also stares into the depths: abysses keep Zarathustra even more preoccupied than mountains.

He who coolly faces the abyss like an eagle shows the existential courage that Nietzsche expects of his Übermensch. “Wer den Abgrund sieht, aber mit Adlers-Augen, wer mit Adlers-Krallen den Abgrund fasst: Der hat Muth” — “He who sees the abyss, but with eagle’s eyes, who with eagle’s talons grasps the abyss: he has courage” (Nietzsche 1895, 6:230, 419). Courage can kill death if it first kills all pity. After all, the deepest abyss a man has to overcome is that of compassion. For Zarathustra, the only way towards eternal life lies hidden behind this superhuman endeavor.

The “Terrible Beauty” of God’s Creation

Kuyper, for his part, also stared into the depths. On one or two rare occasions he witnessed the start of an avalanche from above, as it went down with devastating power, crushing everything in its way. He preferred to look upwards. What Kuyper observed there, at the slopes of Mont Blanc and other giants, had a tremendous impact on his thought. In an 1889 meditation on the “roar of your waterfalls” — Psalm 42 — the images flow freely. In the high mountains, everything testifies to God’s grandeur: the eternal snow and glaciers, avalanches thundering down, the lightning just above your head, but also the depths of the valley below. Yes, in that vast, majestic world, where man is nothing, even the cliffs and the clefts, the eagles and the leaping goats bear witness to the grandeur of God. “Everything is solemn and divinely silent at those heights” (Kuyper 1889a).

Yet, he doesn’t simply take God’s grandeur for granted, but follows a more existential path towards his conclusions. Like his silent mountaineering companion Zarathustra, what he saw before his very eyes was also a superhuman endeavor, but one that leads him to a different position in life.

His first biographer, Pastor Winckel – whose effort, published in 1919, was reviewed by Kuyper himself – had once talked to him about his mountaineering. What actually drove him? It was the only time Kuyper put into words what his tours meant to him. As you ascend, he said, you see the vista becoming more and more beautiful and delightful. That awakens the impulse to want to go higher and higher. But there comes a moment when you can’t go any higher, when the “soaring peak” that glitters in the sun in front of you remains unreachable — even as you know that the view up there would be sublime (“the most delightful panorama,” Winckel noted [1919, 97–98]).

That is, says Kuyper, the moment that it dawns on you that the creation is not there primarily because humans enjoy it, but because that is how the divine shows itself. In the high mountains you literally, physically, encounter the limits of human experience. But precisely in this way, through your very limitation, you catch a glimpse of God’s reality. Courage for Kuyper was this insight, not that of Zarathustra, whom he would often accuse of pride. Or Nietzsche himself, whom he would on occasion portray as the personification of the social Darwinism of his day.[12]

He had previously made the same point — in his own words, in 1888 in Calvinism and Art — but written in general terms, without the reader knowing that he was describing his own experiences (Kuyper 1888, 13). Again, a characteristic passage rolled out, typical of his entire way of thinking. Moreover, it was written immediately after a summer when, as in Nietzsche’s case for the last time, Kuyper had been back in the Alps. “He who has ever enjoyed the rapture,” he writes, “of contemplating the majesty of God’s creation on one of those Alpine peaks covered with eternal ice, realizes with overwhelming urgency the folly of imagining, even for one moment, that only to our human eye this glittering jewelled splendour would glisten on its glaciers” (Kuyper 1888, 13). In the mountains it is impossible to imagine yourself the prince of creation, let alone an Übermensch who with eagle eyes defies the abysses of existence.

Kuyper did not look into the abyss. He looked up. There lay his ultimate vista, the crux of his experiences in the Alps. What was it? It was not his own greatness, but rather the greatness of the divine not-I. In Kuyper’s words, “No, even the Beautiful and the Delightful exist first of all for the sake of God. How would He, who first conceived this beauty for creation and then created beauty into it, have no sense or eye for the effulgence of His own θείότης [divinity] in created being?” (1888, 13). The meaning of God’s creation was contained within itself. What you saw shining before you in the sun was literally the effulgence of that divinity. But in this effulgence God’s love for all creation was imbued. In this way you also discovered who you were, but differently from Zarathustra.

These were the two occasions when Kuyper opened up and expressed what was on his mind on the flanks of Mont Blanc where he often walked — and we can infer that he had gone high here as well, higher, probably, than 13,000 feet or 4,000 meters. Fortunately, it was not the only time he put his impressions into words. But all the other times he did so in the form of images, usually in his meditations and always lyrically. In his aforementioned reflection on the roaring streams of Psalm 42, he sketched the high mountains as “so lofty, so divinely great, so solemn and divinely quiet.” “Silent, holy quiet it is on those mysterious highlands,” where man is nothing and only God’s creation full of majesty (Kuyper 1889a).

The vista from an Alpine peak transcends all other experiences of nature, Kuyper recalled in a meditation on Colossians 3:1, “Above, where Christ is” (1909). He himself had often enjoyed the “delight of beholding, on one of those Alpine peaks covered with eternal ice, the majesty of God’s creation” (Kuyper 1888, 13). Even of the mountain peaks of Jotunheim in Norway, where he had nearly met death in 1883, he remembered above all the “terrible beauty” — in those words (Kuyper 1905, 70).

See e.g. Safranski (2000), Kaag (2018).

Nietzsche’s letter to Peter Gast (Heinrich Köselitz), Sils-Maria, Monday, September 3, 1883 (Levy 1921, 169).

Family letters from 1876, 1882, 1884, 1885, 1886, 1888 and 1887, in collections 36 and 37 of the Abraham Kuyper’s Archive [hereafter AK], see Kuyper (1858–1920). Kuyper’s correspondence in AK cited in this essay can also be accessed online at Neo-Calvinism Research Institute (NRI), https://sources.neocalvinism.org/archive.

All derived from family letters in AK, especially AK 27–53.

Letters to Jo Kuyper-Schaay, dated August 8 (from Sulden), August 15 (from Göschenen), and August 22 (from Chamonix), AK 37.

Letter to Jo Kuyper-Schaay from Göschenen, Switzerland, Sunday, August 15, AK 37.

Letter to Groen van Prinsterer, March 7, 1873 (Goslinga 1937, 217–18).

From his meditation on Is. 54:12 (Kuyper 1889b, 212).

Final letter to Jo Kuyper-Schaay from Luchon (France), Saturday evening, 6 o’clock (August 5, 1899, in the handwriting of Henriëtte Kuyper), AK 38.

I related the complete story in my book The Seven Lives of Abraham Kuyper: Portrait of an Enigmatic Dutchman (Snel, forthcoming).

“Nietzsche is more or less the Multatuli for Germans” (Kuyper [1892] 1998, 5).

About Nietzsche as a social Darwinist, see Kuyper’s speech as prime minister at the occasion of the opening of the academic hospital in Groningen (Kuyper 1903).