Introduction[1]

During the period 1880 to 1940 the Reformed denomination of the Gereformeerden made significant contributions to institutional healthcare in the Netherlands. But these contributions were remarkably unequal: The Gereformeerden provided facilities for ten times as many patients in psychiatric hospitals as in general hospitals.[2] Similarly, the number of new psychiatric hospitals founded by the Gereformeerden far outstripped the number of general hospitals they established. How can this remarkable disparity be explained? This article will argue that ultimately the influence of theological views played a decisive role, as appears when one considers two key Gereformeerde actors, Lucas Lindeboom and Abraham Kuyper.[3]

A few remarks will help to understand the historical background of institutional healthcare in the period. In the Netherlands, private organizations obtained the legal right to establish hospitals in the Napoleonic era. The nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw the institution of an increasing number of hospitals with a confessional identity. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the “Age of Restoration,” this only happened piecemeal. After the adoption of the new constitution in 1848, however, the revival of the Roman Catholic Church and the onset of several revival movements within the Protestant churches gave rise to a surge in new hospitals. Leaving aside the founding of several Jewish hospitals, we can observe that this latter period is characterized by a threefold pattern: Roman Catholic hospitals, Protestant hospitals, and so-called neutral, mainly government-run hospitals without any confessional affiliation.

This article will focus on a particular Protestant church denomination, the Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland (GKN). This denomination was the product of the 1892 union between two secession movements that had issued from the Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk, namely the Afscheiding (Secession) of 1834 and the Doleantie of 1886 (Endedijk 1990, 1:28–39). During the period under consideration, the share which the GKN along with some smaller Reformed denominations had in the Dutch population amounted to roughly 9 or 10 percent.[4] It seems practicable to focus in this investigation on the Gereformeerden, those associated with the GKN, even though the Reformed are properly speaking a somewhat wider group,[5] because the GKN was the only Reformed denomination that took part in the founding of hospitals.

As already mentioned, and as will be detailed in the next section of this article, remarkable quantitative differences emerge when we compare the participation of the Gereformeerden in the supply of psychiatric hospital facilities versus that of general hospitals. Explaining these differences is by no means obvious but has so far received no scholarly attention. Scholars have, however, given some consideration to related questions about religious denominations and the founding of hospitals in the Netherlands. For example, during the period under study (1880–1940), the respective contributions of the Roman Catholic Church and of the Protestant churches to the founding of hospitals were unequal. Some authors have argued that the strong, centralized authority of the Roman Catholic Church is to be credited for the successful institution of so many Catholic hospitals (Hallema 1956; Drogendijk 1975, 44–45). By contrast, the Reformed segment of the population, the Hervormden as well as the Gereformeerden, trailed the performance of their Catholic counterparts in establishing hospitals. Some scholars have suggested that a certain “laxity” explains this lagging (Landelijke Stichting voor Protestantse Ziekenhuisverpleging 1947–1973, passim; Hallema 1956, 347, 351, 384–85). The insufficiency of such an explanation for the present question will be noted later in this article.

The influence of theological views offers another avenue of explanation. After all, the founding of both psychiatric and general hospitals was, for the Gereformeerden, religiously motivated, suggesting a role for theology in their disparate achievements. The possibility that the views of Abraham Kuyper might have shaped Reformed involvement in the establishment of healthcare institutions has been broadly implied by the medical historian M. J. van Lieburg. According to Van Lieburg, Kuyper saw no place for institutional health care in his notion of a re-Christianized nation (1990, 13–14). The present article will contend that Kuyper’s ideas indeed had practical consequences and that his theological views were significant for the disparities in the establishment of Gereformeerde hospitals. Of course, such a theological explanation does not discount the contribution of social factors with a more mundane character like legislation, demographic and geographic conditions, and finances. But the role of these factors, this article will argue, was indirect and, overall, not conclusive.

This article is divided into five sections: The first section provides a statistical assessment of inequalities in the churches’ participation in hospital care. The next section investigates Lucas Lindeboom as protagonist of the founding of Gereformeerde psychiatric and general hospitals. The third section suggests an antagonist of these views in Abraham Kuyper and his theologically inspired perspectives on illness and medical care. In the fourth section, additional factors that help to explain the inequalities are surveyed. Finally, some conclusions are suggested.

I. Assessment of Inequalities in the Churches’ Participation in Hospital Care

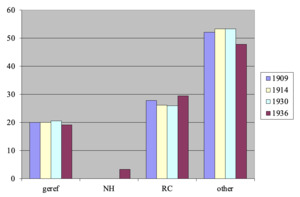

In this section, I offer a more detailed assessment of the participation of Roman Catholic, Protestant, and neutral organizations in hospital care. As shown in Figure 1, the relative share of these three main categories remained largely constant until the beginning of the Second World War.[6] However, the absolute number of beds in general and in psychiatric hospitals underwent substantial growth. At the same time, hospitals gradually developed from almshouses for the poor and sick into modern centers for diagnosis, nursing, and medical treatment (Van Lieburg 1986, 7–41).

The pattern of the Roman Catholic Church, Protestant churches, and the “neutral” people without any church affiliation constituted the basis for the so-called pillarization of Dutch society. Each pillar ran its own social organizations in politics, education, press, and labor movement. Likewise, Roman Catholic, Protestant, and neutral hospitals each had their own societies and their own periodicals. The national government also structured its collection of statistical data for hospitals and hospital beds according to these pillars (Hoofdinspecteur van de Volksgezondheid 1922–1970; see also https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline). As such, these statistics form an indispensable tool for the study of the Dutch hospital world (Dekker 1992, 38; Kennedy 1993, 13–16; Blom 2000, 207; Kruijt 1965, 12; 1959, 11).

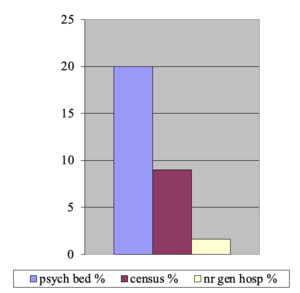

The Gereformeerden in general were eager to expand their influence on Dutch society so as to match or even surpass their share in the population. Their motivation in this was expressed by the famous words of Abraham Kuyper: “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry: ‘Mine!’” (Kuyper 1880b, 35; trans. Bratt 1998, 488). However, when it comes to general hospitals, the Gereformeerden found themselves stranded at no more than 2 percent of all hospitals, while they took on the management of no less than 20 percent of all psychiatric hospital beds (Figure 3). In view of their pursuit of a robust presence in Dutch society, this discrepancy is most remarkable and indeed prompts the present investigation. Since pillarization is a typical, albeit not exclusively, Dutch social phenomenon, we will only consider the Dutch context here, in the expectation that it may also shed some light on issues that are relevant outside the Netherlands.

II. Protagonist: Lucas Lindeboom and the Founding of Gereformeerde Hospitals

Lucas Lindeboom (1845–1933), an ardent follower of the Secession movement of 1834,[7] served in the pastoral ministry from 1866. In 1883 he was appointed as an instructor, and later as a professor, at the seminary—first known as the “Theological School” and later as “The Theological High School”—of the GKN in Kampen. His vocation as a theologian did not dampen his passion for ministering to the spiritual and practical needs of communities. More even than Abraham Kuyper, Lindeboom devoted himself to organizing and promoting charitable causes, and soon rose to a position of power and influence in the development of Gereformeerde social care.

Lindeboom was troubled by the terrible conditions in which most psychiatric patients had to live at that time. He attempted to push the synod of his church to set up Christian institutions for them. These efforts remained unsuccessful, however, until Kuyper wrote a series of five articles on the occasion of the Dutch parliament’s enactment of a new bill on care for the mentally ill (Kuyper 1882; cf. Quak 1987). Kuyper’s articles advocated subjecting the power of judicial admission to psychiatric hospitals to several conditions. According to Kuyper’s proposal, admitting a patient to a psychiatric hospital should primarily be decided by the patient himself, his family, his family doctor, his minister and his legal representatives. Only with the approval of all these parties could a judge then make the final decision. Of course, such a laborious procedure would have substantially curtailed admission to psychiatric hospitals and would have left only a marginal supervisory role for the judge. These proposals, as will be seen later, fitted well with Kuyper’s views about caring for the sick, but they lacked wider appeal and were not adopted by the legislators. Lindeboom and a group of sympathizers seized the momentum generated by Kuyper’s articles, however, to launch a foundation to organize Protestant—essentially, Gereformeerde—psychiatric institutions. In 1884, the Vereeniging tot Christelijke Verzorging van Krankzinnigen en Zenuwlijders in Nederland (Society for Christian care of insane and neurotic patients; henceforth VCK) was established (G. A. Lindeboom and van Lieburg 1984, 23–42). Lindeboom remained its president for almost fifty years, until his death.

Under Lindeboom’s leadership a nationwide network of charity institutions came into being. Eventually, in 1918, these institutions were unified in the Gereformeerde Bond van Vereenigingen en Stichtingen van Barmhartigheid in Nederland (Reformed Union of Societies and Foundations for Charity in the Netherlands). Besides a series of psychiatric and general hospitals, the Bond encompassed a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients, as well as institutions for the blind and deaf, and for mentally disabled children and adults (L. Lindeboom et al. 1927).

Psychiatric Hospitals

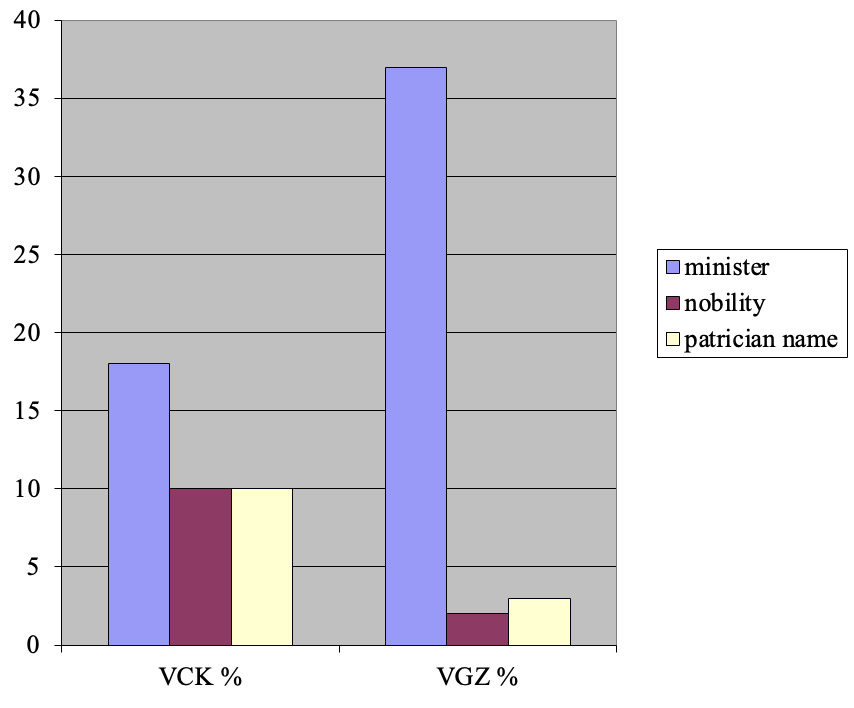

Although a strict proponent of the GKN, Lindeboom preferred to provide a broader base to the VCK by grounding its constitution on the traditional confessional forms of the Reformed church (the Three Forms of Unity) as adopted by the Synod of Dordt in 1618–1619. In this way, a formal connection with a particular denomination could be avoided. Lindeboom was very successful in creating a solid social basis for his VCK. During the period 1882–1940, a total of 104 men (no women) served as members of the board. Among them were nineteen ministers, ten members of the Dutch nobility, and ten men with patrician names (Figure 6). Data regarding their confessional affiliation, however, are not available (G. A. Lindeboom and van Lieburg 1984, 47–48, 388–89). The Gereformeerde share of all psychiatric beds remained at a steady 20 percent in the period 1909–1932 (Figure 4).

As he demonstrated in the general assembly of the VCK in 1887, Lindeboom harbored high expectations for the healing force of the Gereformeerde faith (L. Lindeboom 1887). In his view, the Christian faith enables one to integrate clinical observations with true knowledge by the light of Scripture. As such, new insights are to be expected from Gereformeerde psychiatry. Therefore, so Lindeboom concluded, we need a medical faculty at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam (Free University; henceforth VU), and above all a chair of psychiatry (L. Lindeboom 1887). As long as this was not yet feasible, the task of developing such a Gereformeerde psychiatry rested on the shoulders of the psychiatrists of the VCK hospitals. Eventually, to Lindeboom’s bitter disappointment, lengthy debates did not result in a clear definition of Gereformeerde psychiatry. Nevertheless, he stuck to his views on Gereformeerde psychiatry for the rest of his life (L. Lindeboom 1919, 1932).

Academic Aspirations

In order to create an institute for the education of Gereformeerde psychiatrists, a psychiatric clinic called the Valeriuskliniek was established in Amsterdam in 1910 in cooperation with the VU. It was Lindeboom, not Kuyper, who succeeded in having two professors for the education of psychiatrists appointed at the VU: Leendert Bouman in 1907 (Van Belzen 1989, 37; Sap 1936), and Frederik J. J. Buytendijk in 1913 (Dekkers 1985). Between then and 1960, some 140 psychiatrists obtained their license at the Valeriuskliniek (Wieringa et al. 1960, 35). This first success also fanned the flames of hope for the establishment of a medical faculty at the VU. But two decades later, that fire was extinguished by Lindeboom’s engagement in the debates concerning the nature of Gereformeerde psychiatry and by religious conflict in the form of the so-called Geelkerken controversy.[8] Buytendijk and Bouman left the VU in 1924 and 1925, respectively. The departure of these two respected professors put an end to all expectations for a medical faculty at the VU for the next several decades. Another effect of the Geelkerken controversy was the departure of several Hervormde staff members at the Wolfheze clinic (Van der Spek 1952, 19–27). In 1927 they established their own Hervormde organization for psychiatry, which eventually succeeded in managing three large psychiatric hospitals (Brouwer 1952, 28–32). There can be little doubt that this development further curbed the expansion of the VCK.

The Gereformeerde Nature of the VCK

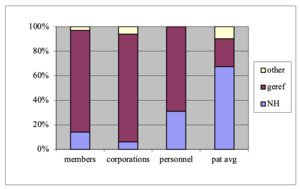

One might ask to what extent the institutions of the VCK were just broadly orthodox Protestant in nature or more specifically Gereformeerd in character. Membership was open to all adults, men as well as women, who agreed to the VCK’s statutes (art. 3, statutes of the VCK, as quoted in L. C. Lindeboom and Wielenga 1935, 77–78). The denominational affiliation of the majority of these members has been documented for one year; in 1916, 83 percent were Gereformeerd and 14 percent were Hervormd (G. A. Lindeboom and van Lieburg 1984, 110). Members could unite in local committees (mostly church councils) so as to form a corporation. In 1909, 86 percent of these corporations were Gereformeerd and 8 percent were Hervormd (L. Lindeboom 1910, 63). The numbers for the nursing personnel show a greater divergency; in 1909, 69 percent were Gereformeerd and 31 percent Hervormd. Most remarkable is the denominational affiliation of the patients: The average for the period 1909–1932 shows that 25 percent of patients were Gereformeerd and 70 percent Hervormd (Figure 5). This allows us to conclude that the VCK was essentially a Gereformeerde organization, though the vast majority of its “clients” were Hervormd. The high percentage of Hervormde patients can be explained by the fact that they constituted a far greater share of the Dutch population, and by the absence (until 1930) of specifically Hervormde psychiatric institutions.

Gereformeerde General Hospitals

Three Gereformeerde organizations for general hospitals were established. The Vereeniging tot bevordering van Gereformeerde Ziekenverzorging in Nederland (Society for Gereformeerde patient care, est. 1893; henceforth VGZ) had nationwide aspirations like the VCK. As both organizations had the same founder in Lucas Lindeboom, they are comparable. The two others were Eudokia in Rotterdam (1890) and the Vereeniging voor Gereformeerde Ziekenverpleging (Society for Gereformeerde patient nursing) in Amsterdam (1894), which were both initiatives of local church charity (diaconie). The latter two focused on local and regional care, and were intended to manage a single hospital only. In the course of study, archival material was found for all hospitals. The VGZ published annual reports and short communications in its monthly, Bethesda. Memorial books were published by all hospitals on the occasion of jubilees. While there is secondary literature for the VCK, this is not the case for the Gereformeerde general hospitals.

The VGZ

The VGZ was instituted in 1893 in Utrecht. Its objectives were to provide home nursing services and to found hospitals, preferably one in each province of the Netherlands (Vereeniging voor Gereformeerde Ziekenverpleging 1893–1902; Kooistra-van der Lelie and Dijkens-Plette 1992, 4–9). In the end, however, the VGZ only succeeded in founding two rather modest hospitals in rural areas: Salem in Ermelo, and Bethesda in Hoogeveen. In contrast with the VCK, the members of the VGZ board were predominantly clergymen; for the period from 1893 to 1940, the cumulative clergy membership was 37 percent. Only a few noblemen and men with patrician names took part in this board (Figure 6).[9]

The Diaconal Hospitals

In Rotterdam, the local Gereformeerde diaconie opened Eudokia, an institution for the nursing of patients with chronic diseases in the province of Zuid-Holland (1890). Within several years, it developed into a respectable midsize urban hospital. As in the VCK hospitals, the number of Hervormde patients surpassed that of the Gereformeerde patients (Kruyswijk 2020, 106). One remarkable event in its history was Abraham Kuyper’s visit to Eudokia on the occasion of its twenty-fifth anniversary in 1915 (Bornebroek 1989, 92–94, 280–305). Before an audience of some 1,200 men and women he delivered a festive address lasting two hours, whose text will be referred to later on.

In 1891, another Gereformeerd hospital was set up in Amsterdam by the Amsterdam diaconie. Eventually its capacity grew to 240 beds, thus constituting a medium size urban hospital (Dooyeweerd 1954, 5–29). After a royal visit from Queen Wilhelmina and her daughter Princess Juliana in 1928, the hospital changed its name to Juliana Ziekenhuis (Dooyeweerd 1954, 25). In 1919, the VU looked for opportunities to expand its partial medical faculty with a chair for internal medicine. As such, with the two professors of psychiatry already on board, the VU would meet the criteria for the establishment of a fourth faculty by 1930, as stipulated by the Higher Education Act of 1905 (see also the next section). The obvious solution seemed to be to turn the Juliana Ziekenhuis into an academic hospital. Raising the funds necessary for this plan, however, proved to be far beyond the reach of both organizations, and so the plans for a medical faculty at the VU had to be dropped (Dooyeweerd 1954, 24; Juliana Ziekenhuis, Minutes board meeting, April 28, 1919 and January 26, 1920; Juliana Ziekenhuis, Jaarverslag, 1920, 1921). In 1930, the VU was able to meet the legal criteria by establishing a much cheaper faculty of science.

The Success of Gereformeerde Psychiatric Hospitals

In short, with respect to psychiatric hospitals Lindeboom achieved resounding success in pursuing his vocation of charity. His organizational talent activated Gereformeerde institutions to take advantage of the rapidly expanding demand for psychiatric facilities following the new legislation regulating psychiatric care. Moreover, the absence of the Hervormden in institutional psychiatry guided many Hervormde patients toward Lindeboom’s institutions. In the case of Gereformeerde patients, the fact that admission to a psychiatric hospital was according to the new legislation determined by the decision of a judge, meant that the inflow of patients was not inhibited by theological considerations such as the views of Kuyper.

As we will see in the next section, in the field of general hospitals the practical operation of theological considerations was not similarly overruled by the effects of legislation. As a result, theological considerations remained influential and to a large extent discouraged the expansion of Gereformeerde hospital care.

III. Antagonist: Abraham Kuyper’s Views on Illness and Medical Care

Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920) was the unsurpassed leader of the Gereformeerden of his time (for Kuyper, see Koch 2006; Snel 2020, 2023). But Kuyper was not inclined to promote the institution of Gereformeerde hospitals. I will argue that this must be ascribed to his theologically motivated views on illness and medicine and on natural science in general. In the following section, I will discuss Kuyper’s view on care for the sick, along with his views on the wide range of medical treatment from traditional to scientific medicine, the place of medicine in the university order, and the role of professional nursing and medical doctors.

Original Sin

According to Kuyper, the primary cause of disease, as of all evil, is man’s Fall in paradise. As a result, God’s curse came over the whole of creation. In his grace, however, God limited the effects of his curse. By his common grace, God’s creation would not be destroyed completely but maintained, albeit in a defective state. Moreover, God offers his particular grace to humankind by his Word, the Bible, and by sending his son Jesus to the earth as savior. The mainstay of the Gereformeerde faith is the Bible as God’s own, absolutely trustworthy word (Kuyper 1904, 422–25, 430–31, 677–83).

Illness as a Life Event

Kuyper primarily viewed illness as an existential crisis that one had to cope with by one’s religious way of life, not as a challenge for scientific study. In 1901 he issued a monograph on home care entitled Drie kleine vossen (three little foxes), which was intended for Gereformeerde households. In this book, Kuyper offers an empathetic and intimate look into family life with a sick family member at home. He depicted in vivid colors the role of the ill pater familias in the bedroom, as he is cared for by his spouse and daughters, and receives consolatory words spoken to him by the minister of his congregation. It is worth mentioning that Kuyper’s book does not discuss the possibility of illness for the mother or the children. In Kuyper’s view, the utmost should be done so that patients may remain at home. Indeed, according to his vision, illness serves the higher purpose of encouraging the patient as well as his relatives to adopt a more thoughtful life in order to draw nearer to God and to acquire a renewed spiritual attitude (Kuyper 1901, 142–43).[10]

Care and Resistance to Disease

This did not mean, however, that illness was to be seen as a blessing from God. On the contrary, illness was one of the manifestations of God’s curse on creation after the first sin. Since Christ has fully paid the penalty for our sins, Kuyper explained, it is a fundamental error to resign or submit ourselves to evil. One must fight disease with all the means which God himself has provided in nature (Kuyper 2017, 2:423–93 [§61–72]; see esp. 439–43 [§64]). Convinced of the rich promises of common grace, Kuyper trusted in the healing forces hidden in nature (vis medicatrix naturae) waiting to be discovered by man, the offered means (media oblata) (Kuyper 1910b, Locus de providentia 235). Therefore, natural medicine and homeopathy had his warm sympathy (Kuyper 1898, XXXVI, XLI; 1910b, Locus de providentia 235; Kuyper [1908b], 132–34; G. A. Lindeboom 1961, 103–6; Van Bergen 2012). Notably, Kuyper was a strong proponent of smallpox vaccination, which can indeed be seen as deriving directly from nature. Of course, coerced governmental vaccination was unacceptable to him.[11] Professional nursing and the doctor’s aid were to be avoided as long as possible. Hospital admission was acceptable only in case of the absence of adequate home care, the need for surgery, the presence of contagious disease, or dangerous mental disturbance.

Science and Medicine

Kuyper made a clear distinction between somatic (bodily) and psychic disease. In his university system, psychic disorders belonged to the domain of the faculty of humanities (Kuyper 1892, XL). On one occasion he argued before his junior VU-students that somatic disorders should be the object of medicine, as they belong to the natural sciences. As such, they pertained to the lowest level of the university, its basement (sousterrein). Kuyper completed the figure of this structural image of the university by attributing the higher levels to the “spiritual science of invisible human life” (Kuyper [1900], 17). In Kuyper’s Encyclopaedie he stated that empirical natural science was, essentially, not very different from the farmer’s empirical knowledge of agriculture and cattle-breeding (Kuyper 1908, 2, 105). One may ask why Kuyper held the natural sciences in such low esteem. Two further statements are elucidating in this regard. First, in 1893 Kuyper wrote in De Standaard: “Theology is not only the first one of the sciences but also the only one that straightforwardly and completely affects the human heart. … The other sciences, especially the ‘positive’ and the ‘exact’ sciences, do not do this at all” (Kuyper 1893). In a parliamentary address of 1904, Kuyper argued in a description of the university order that natural science, as opposed to theology, law, humanities, and even—presumably, somatic—medicine, stands “completely outside human life.” This time he presented the university using an organic metaphor, depicting it as a human body with a head (theology), arms (law and medicine), and legs (natural science and humanities) (Kuyper [1910c], 7).

Science cannot content itself with “the first and lowest part of their studies,” namely mere observation and measurement. Kuyper later argued that this was something Darwin’s evolutionary theory had already demonstrated. Observations are to be integrated into general laws, thereby elevating science to its second stage, which is the philosophy of nature as the culminating discipline in this faculty (Kuyper 1908, 2, 105, 159–60). This notion of a higher and lower scale among the sciences and faculties seems to fit quite well with Kuyper’s concept of a “twofold science” (tweeërlei wetenschap): “normalist” science, and “abnormalist” science (Kuyper 1908, 2, 102–11; 1899a, 143–88; see 172–86[12]). The science of the normalist is autonomous and respects intrinsic scientific law only. The abnormalist has to fit into his religious worldview the results of his scientific study, which as such of course do not differ from those of the normalist.. For him, the laws of nature are not inherently natural, but they have been laid in nature by God himself and embedded in creation as so-called ordinances (ordinantiën) (Geesink 1907, 1:10–27). We may conclude that there are, according to Kuyper, differences between faculties as far as the degree of their philosophical integration and their distance to the “human heart” are concerned. In his figurative university building, this distance is measured on a vertical scale, where theology occupies the penthouse on the top floor, while natural science is found below in the basement. Just like natural science, so Kuyper argued, the faculty of medicine should find its “highest unity” in its respective philosophy of science (Kuyper 1908, 2, 150, 161).[13]

Evolution

Apart from its low standing in the university order, science—and, for that matter, somatic medicine—could constitute an outright danger for the Christian belief in God’s permanent governance of the world and of human life. Indeed, unsurpassable problems surfaced when scientific theory proved incompatible with theologically based convictions like those regarding the age of the universe or humanity’s descent from animals. In his very last academic address, Evolutie (Kuyper 1899b, trans. Bratt 1998, 405–40), Kuyper adamantly rejected Darwin’s evolutionary theory. Admittedly, at that time it was still a theory, albeit one with a rapidly increasing degree of probability and scientific support. Kuyper furiously denied its essential composing parts of spontaneous variation and natural selection by survival of the fittest. He raged against the idea of a random process of evolution of the natural world apart from God. For Kuyper, due to his unswerving adherence to the plain historical authority of the Holy Scripture, evolution obviously was an inaccessible road (Kuyper 1899b; see also Kruyswijk 2011, 44–53). In fact, to his mind it represented a frontal attack on belief in God’s purposeful creation of the world as recorded in Genesis. In an ultimate attempt to allow for the possibility of development in nature, he suggested that if God had designed a foregoing species to the production of the higher next one, then “creation would have been just as wonderful” (Kuyper 1899b, 47; trans. Bratt 1998, 436–37). But that, of course, was exactly the opposite of Darwin’s theory of evolution as a random natural process.

The opening sentence of Kuyper’s Evolutie address reads: “Our nineteenth century is dying away under the hypnosis of the dogma of evolution.” Kuyper appealed to his listeners to wake up from this frightening hypnosis. But, and here I must disagree with Kuyper, one should take into consideration that the evolutionary theory is primarily not a theological dogma but a scientific theory based on numerous observations and the logical elaboration of these observations. A scientific theory can be challenged by scientific methods only. Is that not the consequence of the principle of sphere sovereignty? And so, Kuyper started to object to the evolutionary theory with scientific counterarguments taken from other authors—he himself was, after all, not a biologist (Kuyper 1899b, 17–38; trans. Bratt 1998, 418–31). But that was not the core of his concern. His rage was directed against the extrapolation of scientific observations into a general theory of descent by a random process of natural selection. Next to his objections based on natural science, now came his counterarguments derived by deduction from theological conviction. That would have been adequate if the evolutionary theory had been a dogma or a belief, as Kuyper stated (Kuyper 1899b, 7, 8, 50; transl. Bratt 1998, 405–7, 439). But he mistook a scientific hypothesis for a dogmatic statement, and an ominous one at that (Kuyper 1899b, 50–51; trans. Bratt 1998, 439–40).

Science and Faith

In his Stone Lectures, Kuyper had said that there is no conflict between science and faith; the conflict is rather one between so-called normalist science and abnormalist science (Kuyper 1899a, 173). There seems to lie the key to understanding Kuyper’s general attitude toward natural science. He not only had a condescending view of science, but he plainly condemned what he perceived as an undermining of faith in God’s command of natural history and human life. Time and time again he argued that everything that happens in the world occurs by God’s will, by his providence. The laws of nature are part of his permanent government. When a stone falls down, that happens because God pulled it that way. When a tree grows up, it is because God pushes it upward. It is God who directs the world as if playing the keys on a piano. If a miracle occurs, it is because God on that one occasion is playing a melody other than the usual one. Not a sparrow will fall to the ground without God’s will. When a clock runs by the force of a spring, it is God who continuously provides the force in that spring. Illness is also sent to us by God himself; it is he who sends the diphtheria to my child. As Kuyper put it, “He is not only the exclusive master of medicine but also the only one who makes you ill.”[14] And so, one may remark, if evolution could turn out to be a random process, could catching diphtheria not also be a random effect of natural law?

In a study of Kuyper’s address on biblical criticism (Schriftcritiek), the VU theologian C. Augustijn argued that Kuyper could not live without the absolute certainty which he derived from the absolute infallibility of the Bible. The very idea of uncertainty filled him with an existential fear (Augustijn 1998, 120, 147).[15] In order to demonstrate Kuyper’s adoption of the priority of faith over science, Augustijn (1998, 116) referred to Kuyper’s response to a letter from J. H. Gunning: “Science should be free. We only demand that the community of Christ should maintain its freedom to accept or to reject the results of science. The community does also investigate the truth, but it follows the path of faith, love, and prayer. Results obtained in this way provide higher certainty than the results of scientific investigation” (Kuyper 1873). But this magic formula, in my opinion, is not consistent with the principle of sphere sovereignty. By this statement Kuyper declared himself off-side, as it were, pretending to be invulnerable to the rules of the discourse of scientific thought.

To prevent cognitive dissonance, would a better solution not have been to include the randomness—“tuchè” as Kuyper calls it (Kuyper 1899b, 13)—connected with natural law into a more encompassing concept of common grace? Indeed, the more the normalist’s hypothesis was to gain the status of generally accepted scientific facts, the less the abnormalists would have to be “tyrannical,” to retreat, and to adopt broader views.[16] It took far more than half a century before VU biologist Jan Lever, after a long struggle, concluded that creation as well as evolution had to be accepted in thanksgiving as wonderful gifts from God (Lever 1956, 2010; see also Kuitert 1970, 151–62).[17]

Doctors and Scientists

After the foregoing observations, it should come as no surprise that Kuyper did not have much sympathy for scientists and medical doctors. The latter were the object of several critical and even ridiculing remarks, for example in Kuyper’s introductory address before the VU-Vereniging in 1892. According to Kuyper, “three-quarters of the so-called medical science could very well be left to the heathens and Turks. … For a febrile patient it does not matter at all whether the quinine is administered to him by a Peruvian or by a learned doctor.”[18] Most doctors were “materialists” (Kuyper 1892, XLII).[19] A notable exception in this regard was the praise Kuyper heaped on Robert Koch’s studies on tuberculosis (Kuyper 1892, XLI).[20] Kuyper also wrote several articles in De Standaard to propagate his adverse view of the medical profession, culminating in an article entitled “The Mercilessness of the Medical Profession” (De onbarmhartigheid van den geneeskundigen stand) (Kuyper 1878a, 1878b, 1880a).

In no way, however, do these views mean that Kuyper was blind to the results of the natural sciences and medicine (Kuyper 1899b, 165–72). For his address on evolution it is clear that he had made a thorough study of the relevant literature (Lever 1956, 188). Not without pride did he claim the inventions of the telescope, the microscope, and the thermometer as the results of the Dutch Calvinist sense for science (Kuyper 1899b, 146). In his Eudokia address he boasted that most, if not all, recent medical advances owed their existence to “Christian territory” (Christenland) in Europe and America. Admittedly, not all inventors had been Christians themselves, but it was the Christian principle that had enabled the general development of the human mind (Kuyper 1915, 16–17; trans. Kuyper 2024, section III). An enthusiastic traveler and mountaineer, Kuyper made ready use of modern means of transportation (Snel 2020, 56–132). And, most strikingly, Kuyper is reported to have sought medical assistance for himself rather eagerly and at quite frequent intervals (Kuyper 1898, 39; H. S. S. Kuyper and J. H. Kuyper 1921, 163–69; G. A. Lindeboom 1955, 37).[21]

How can one explain that Kuyper, notwithstanding his low esteem for and mistrust of medicine and the natural sciences, still made such eager use of their apparently convenient benefits? We may assume that he appreciated them as gifts of common grace, even as a straight blow with a crooked stick, which were to be accepted with thanks. As we have noted, they were in essence the effects of the “Christian principle.” In his Eudokia address, Kuyper moreover maintained that medicine is nothing but an automatic reaction from creation against the evil consequences of original sin. In this proposition, “the indispensable knowledge and efforts of the scientist and doctor are completely played down” (Kuyper 1915, 22; trans. Kuyper 2024, section IV; cf. G. A. Lindeboom 1955, 37).

During his term as prime minister (1901–1905), Kuyper conveniently passed a law in parliament stating that newly founded universities, of which the VU was the only example at the time, could meet the demands for government recognition with three faculties only. A fourth faculty only had to be instituted after the university’s first fifty years.[22] In the case of the VU, this meant that the faculties of science or medicine did not have to be established until 1930. In the meantime, Gereformeerde doctors and scientists were educated at state universities in increasing numbers. Kuyper blocked advertisements for these studies in De Standaard. Moreover, he never addressed Gereformeerde student societies at state universities, like the Societas Studiosorum Reformatorum (SSR, est. 1886; Society of Reformed Students) or the Christelijke Vereeniging van Natuur- en Geneeskundigen (CVNG, est. 1896; Christian Society for Scientists and Medical Doctors), or the medical institutions founded by Lindeboom (Puchinger 1961, 17; De Bruyne 1961, 107; Van Bergen 2005, 141). Although Kuyper did not overtly try to prevent the institution of Gereformeerde hospitals, he did for some time effectively discourage the institution of a chair for psychiatry at the VU in Amsterdam (Kuyper 1892, XXXVI–XLII; see also Van Lieburg 1990, 8).

In summary, according to Kuyper, care for the sick was first of all a matter of private charity within the family sphere. Although he held science in general in high esteem, this estimation did not always equally extend to the natural sciences and medicine. We pointed in this regard to the role of Kuyper’s theological ideas and his notions of normalist and abnormalist science. We also noted indications that Kuyper was wary of the conclusions of science that might endanger his existential certainty, based as it was on the plain historical authority of Scripture. Significantly, Kuyper’s views, because of his prestige and authority, exerted a strong inhibiting effect on the creation of Gereformeerde general hospitals. By contrast, since by law the decision of admission to a psychiatric hospital was left to doctors and judges, the potential of these theological views to impede the inflow of patients and concretely shape the growth of institutional psychiatry was minimized.

Comparing Lindeboom and Kuyper

For Kuyper, insanity was primarily a social and legal issue, not a medical one (Kuyper 1882, III and IV; Quak 1987). Lindeboom, by contrast, was above all deeply motivated by compassion for the mentally disabled. His passion was providing practical help, which he explicitly did from a Gereformeerde stance. For Lindeboom, no true medicine or psychiatry was possible outside the Christian faith, preferably the Gereformeerde faith. Indeed, in his opinion, non-Christian medicine was essentially no different from veterinary medicine, without a connection to the patient’s soul (L. Lindeboom 1887, 26). Another difference with Kuyper is that Lindeboom was interested in the development of a systematic analysis of mental disorders. Kuyper, in contrast, appreciated the results of profane science, but he apparently was not very interested if they were not connected to the “human heart.”

To my knowledge, Kuyper’s views on illness and medicine did not generate much of a response in the Gereformeerde press during his lifetime. At the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the VU (1955), however, the founder of the VU medical faculty, Gerrit A. Lindeboom (1905–1986), a grandson of Lucas Lindeboom, himself professor of medical encyclopedia, the history of medicine, and internal medicine and an enthusiastic publicist, offered a critical observation (G. A. Lindeboom 1955; cf. Kuilman 1980, 163; Langevoort 1980, 187–89; Van Bergen 2005, 59–92).[23] G. A. Lindeboom limited himself to two of Kuyper’s publications: the chapter on medicine in the Encyclopaedie, and his Eudokia address.

Lindeboom reminded his audience that Kuyper had stated that the medical faculty attained its “highest unity” in the philosophy of medicine (Kuyper 1908, 2, 147–50). In Lindeboom’s view, by way of contrast, therapy was the primary issue of medicine. Moreover, Kuyper had committed “an evil deed” (een boze daad) when he differentiated between psychic and somatic medicine and when he referred the study of the human psyche to the humanities and “somatic medicine” to the natural sciences.[24] Reducing medicine to natural science had given rise to a real crisis in the development of medicine, so Lindeboom charged. Kuyper had even “secularized” medicine (G. A. Lindeboom 1955, 38). Notably, Lindeboom was a sympathizer of psychosomatic medicine and of the holistic Swiss philosopher and physician Paul Tournier. Upon nomination by Lindeboom, Tournier was awarded an honorary doctorate from the VU (Van Lieburg 1990, 4; Van Deursen 2005, 247). Against Lindeboom’s view, we should remark that Kuyper, to his credit, had stated several times that the primary object of care should be body and soul together, albeit not so much the object of cure. But Kuyper was not at all consistent as far as psychiatry is concerned. According to G. A. Lindeboom, Kuyper felt embarrassed by the adoption of Lucas Lindeboom’s psychiatric clinic into the VU in 1905 (G. A. Lindeboom 1955, 23; cf. Glas 1986).

As G. A. Lindeboom argued, another inconsistency in Kuyper’s view on medicine was his attribution of all progress in medicine to Christian influence (Kuyper 1915, 14–18; trans. Kuyper 2024, section III). This is not consistent with Kuyper’s statement that common grace, not particular grace, is the source of medicine. Moreover, it is a denial of the special input of the physician in general and of the Christian physician in particular (G. A. Lindeboom 1955, 37). It is to be lamented that Christian charity did not appeal to Kuyper as a powerful motive for the study of medicine. In fact, as G. A. Lindeboom also noted, charity and the vocation to help any fellow human being in need notably is the highest motive for exploring all medical possibilities, as his own grandfather Lucas Lindeboom had explicitly argued. In summary, G. A. Lindeboom was not satisfied with Kuyper’s contribution to medicine. In his time, the VU academic hospital adopted the following motto: Medicina misericordiae ministra (Medicine is the servant of charity) (Roelink 1979, 172–73).

IV. Additional Factors

The concrete historical context in which Gereformeerde hospitals were founded was, of course, not only shaped by theological ideas but also by social realities. The question arises to what extent certain social conditions explain the differences in the founding of general and psychiatric hospitals among the Gereformeerden. In other words, to what extent do social factors account for the remarkable difference between the impressive contribution of the Gereformeerden in the field of psychiatric hospitals and their lackluster contribution to general hospitals? The possible influence of a few significant social factors will be briefly considered.

Legislation

Until the mid-nineteenth century, the maintenance of public order had been the main motive for the isolation of insane patients from society. We saw a late echo of this attitude in Kuyper’s articles in De Standaard. From 1841, legislation required the judicial commitment of a person to a psychiatric hospital if ordered by a judge following medical analysis (Kuyper 1882; Van der Esch 1980, 3:67–88; Quak 1987; Oosterhuis and Gijswijt-Hofstra 2008, 45–48, 75–81). Legislation was therefore an influential social factor behind the expansion of facilities for the admission of insane patients, and more specifically led to the creation of more psychiatric hospitals. Because this was true in equal measure for all religious denominations, legislation and legal requirements did not affect Gereformeerde institutions particularly—apart from paving the way for their founding by undermining any possible theological objections, specifically those of Kuyper. In the beginning of the twentieth century, patients’ interests gained more and more attention, and eventually so-called open wards were created for patients not subject to forced hospitalization by legal order.

Ecclesiastical Authority Exerted by Gereformeerde Professors of Theology: The “Sanatorium Controversy” (“sanatorium kwestie”), 1902–1905

After the establishment of four Gereformeerde hospitals, no further institutions were founded. Apart from the general influence Kuyper exercised, another, more formal argument had come from the side of the ecclesiastical authorities. In 1902 the Central Charity Conference of the GKN considered the possibility of establishing of a Gereformeerd sanatorium for patients with tuberculosis. The theological professors of the VU and the Kampen seminary, who served as advisors to the general synod, were asked for advice. Their submission advised negatively: the deaconries should limit themselves to care for the poor, and not the sick. Rather, they argued, Gereformeerd patient care should be delivered by private corporations in conjunction with the church. And thus, as the saying goes, “Rome has spoken, the matter is finished” (Roma locuta, causa finita). This was a heavy blow for the diaconal organizations, which felt deeply undervalued by the church authorities.

On the other hand, as we have seen, hospitals were during this time undergoing rapid development from almshouses for chronically ill and mostly poor patients to centers for surgical and medical treatment. Within a few years of its establishment, Eudokia had detached itself from direct church governance and switched to private management (Bornebroek 1989, 79–81). Therefore, the negative advice given to the synod, notwithstanding its initially high symbolic value, eventually lost most of its importance. Within several years, in 1908, the establishment of an orthodox Protestant sanatorium for tuberculosis patients, Sonnevanck, became a reality (L. Lindeboom et al. 1927, 60–78; Bornebroek 1992, 43–50).

“Laxity”

As noted in the introduction of this article, some scholars have discerned a certain “laxity” which they claim at least partly explains why the Gereformeerden lagged behind Roman Catholics in the establishment of general hospitals. This argument is not convincing, however. In no way can it be said that Gereformeerden were lax when it comes to church organization, education, politics, journalism, and the labor movement; here laxness was a rare exception. Moreover, why would they have been lax in general hospitals, but not in psychiatry? And could this have happened even under Lucas Lindeboom, who held a position of leadership in the establishment of both general and psychiatric hospitals? Laxity, it would seem, can safely be excluded as an explanation.

Church Affiliation and Geographic Factors

As we have seen, notwithstanding their thoroughly Gereformeerde stance, the psychiatric hospitals earned nationwide Protestant support. Until 1930, they faced no competition from organizations with a Hervormd Protestant background. For therapeutic reasons, psychiatric hospitals were constructed in quiet rural surroundings during the period under consideration. Large as they usually were, they received patients from much wider areas than general hospitals did. Therefore, the interconnection of geographic factors with the denominational affiliation of patients did not play an important role for the location of these hospitals.

The target area for general hospitals is more locally restricted, in particular when they also admit patients in need of acute care. For this reason, they need a minimal geographic concentration of patients, like in bigger cities. Generally speaking, however, Gereformeerden were underrepresented in the bigger cities in the Netherlands. It was only in Rotterdam and Amsterdam that the absolute number of Gereformeerde inhabitants was sufficient to maintain hospital facilities without assistance from their Hervormde counterparts.[25]

In several rural areas, however, especially in the north of the country, several clusters of neighboring communities with relatively large concentrations of Gereformeerden could be found. Their absolute numbers should have been sufficient to enable the founding of two or even three more Gereformeerde hospitals. Apparently, other factors, like religious convictions, or more mundane ones, like the need for a considerable number of local church councils to cooperate, may have curbed serious initiative (Kruyswijk 2020, 113–14, Table III.1). In this framework, we also need to recall the differences in the social composition of the boards of het VCK and the VGZ, as discussed earlier.

Competition from Other Protestant Hospital Organizations

As shown in Figure 2, from 1849 on, the Hervormde deaconess hospitals (Diaconessenhuizen) had created a group of general hospitals which in 1940 eventually encompassed eighteen institutions. In Amsterdam and Rotterdam, a Diaconessenhuis and a Gereformeerd general hospital lived in peaceful coexistence. To my knowledge, competition between Gereformeerden and Hervormden occurred in only one instance: In Groningen, the Diaconessen were already running a hospital when the Gereformeerden came with their wish to create their own institution. Since the city was too small for two Protestant hospitals, the Gereformeerden proposed cooperation with the Hervormden in a common institution. The Hervormden, however, were not inclined to do so (Kruyswijk 2020, 97).

Financial Issues

Private hospitals had to be financed by private means.[26] Shortage of funds may have played a role in the failed attempts to found Gereformeerde hospitals in The Hague, Eindhoven, Friesland, Bussum, and several other places. In the same period (1910–1940), however, six more Hervormde Diaconessenhuizen were successfully set up, even in three places where Gereformeerde initiatives had failed before (Eindhoven, Naarden/Bussum, and Voorburg/The Hague). As we have seen, the composition of the denominational affiliation of patients in the Gereformeerde hospitals indicates that the target group for both parties was virtually identical. Therefore, a general shortage of financial support for the founding of a Protestant hospital is unlikely to have been decisive in any of these cases (Kruyswijk 2020, 84, 89–90, 94–98). We may conclude that, in contrast to the Hervormden, the Gereformeerden, despite their celebrated generosity (cf. De Bruijn 1999) were not able to raise sufficient funds for the building of general hospitals. Thus, other reasons than simply financial ones must have played a decisive role. Seen against the background of what we have argued earlier, it does not seem improbable that theological considerations have exerted an inhibitive effect here also.

Another factor that should be kept in mind is that patients were required to pay for admission to general hospitals. Until the Second World War, only a minority of people in the Netherlands had some form of insurance to cover the cost of hospital treatment. But since this was true for the entire population, it did not particularly affect Gereformeerde institutions and cannot, therefore, be considered a contributing factor for the Gereformeerden lagging behind the Hervormden in the institution of general hospitals.

V. Conclusion

At this point, we can return and address the main question advanced at the outset of the article: Why were the Gereformeerden so successful in establishing psychiatric hospitals while lagging behind in founding general hospitals? I have tried to explain this discrepancy by comparing the influence exerted by the two most prominent leaders in this field.

Lucas Lindeboom was a dedicated proponent of practical charity in institutional medicine. He dynamically orchestrated initiatives to practically and institutionally improve the needy situation of mentally ill patients. Under such leadership the Gereformeerde hospital care for psychiatric patients took flight, and came to be firmly embedded in the orthodox Protestant population. Yet despite the advantage given to Gereformeerde psychiatric hospitals by Lindeboom’s leadership the comparatively lagging development of Gereformeerde general hospitals should, this article has comprehensively argued, be explained above all by the inhibiting effect of Kuyper’s ideas. It is remarkable that Kuyper, who had famously exclaimed, "There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry: ‘Mine!’ " (Kuyper 1880b, 35), did not claim the terrain of professional and scientific healthcare for Christ.

To be sure, this explanation does not establish an indisputable causal relationship between Kuyper’s theological views and the historical trends in the founding of Gereformeerde hospitals. But such difficulty is, of course, a more general problem in historical investigation; it is often challenging to demonstrate the causal connection between historical actions and theological ideas. That does not mean that such causality is tenuous, but that a cogent argument for causality can sometimes scarcely go beyond showing a general plausibility and noting strong evidence consistent with the suggested explanation of the influence of theological ideas.

And indeed, the connection between Kuyper’s ideas and the underperformance of Gereformeerde general hospitals vis-à-vis Gereformeerde psychiatric hospitals is a probable one: the two phenomena, Kuyper’s views and the lagging of Gereformeerde general hospitals, are congruent, and they took place at the same time, in the same country and culture, and within the same “pillar” — of which Kuyper was the foremost spiritual leader. If, as this article argues, Kuyper’s ideas, like Lindeboom’s, were influential in the founding of Gereformeerde hospitals, the study of the history of Gereformeerde hospital care may shed additional light on Gereformeerde theology.

This article is a revised and abridged version of Kruyswijk 2020. Part of it was originally presented as a paper at the Kuyper Conference, April 2022 in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

See the statistics discussed in section 1 below.

Apparently, Kuyper and Lindeboom were the only Gereformeerde theologians to play a role in the debate on institutional medicine. Notably, Herman Bavinck did not take part (Dirk van Keulen, personal communication, 2024).

The numerous Hervormden are not in this article categorized as one of the Reformed denominations.

During the period of this study, the GKN constituted some 7% of the Dutch population.

As can be seen in Figure 1, after the Second World War the share of the Roman Catholic as well as that of the Protestant Christian hospital beds substantially increased at the expense of the neutral hospitals.

For Lucas Lindeboom, see Kuilman 1980, 162–63; Langevoort 1980, 187; Van Belzen 1989, 13–23; Van Bergen 2005, 119–143; Van Klinken 2012, 120–46. Lindeboom did not publish books, except as coauthor. Dozens of his addresses, however, have been edited for publication. For a bibliography, see Wiersinga 1940, 67–68.

In 1926 the Gereformeerde minister J. G. Geelkerken was deposed by the general synod of the GKN for his free interpretation of the Bible’s description of the Fall in paradise.

Data collected from the reports (Verslagen) of the VGZ (1905–1938) and from minutes of VGZ board meetings and general assemblies (1901–1942).

The title of this book, Drie kleine vossen (Three Small Foxes), is derived from Song of Solomon 2:15 on the spoiling of vines by small foxes.

In contrast to Kuyper, Lindeboom did not want to have his children vaccinated. Since at that time vaccination was a condition for children to attend primary and secondary school, Lindeboom’s children were educated at home, primarily by their parents. See De Bruijne 2012, 11–14.

In his Stone lectures (Kuyper 1899a), Kuyper did not explicitly discuss medicine.

The expression “highest unity” seems to mean “raison d’être, right to exist.”

For these and more examples that Kuyper gives for God’s permanent governance of all events in the world, see Kuyper 1910a, Locus de creaturis, B: Locus de creaturis materialibus, 20–24; Kuyper [1923], 231–42.

Another example of this fear can be found in Kuyper’s monograph on modernism (Kuyper 1871, 54; trans. Bratt 1998, 122). Here Kuyper quotes several contemporary writers on modernism, concluding that modernism must necessarily result in scepticism and mortal terror: “Am I or am I not?”

“Tyrannical” was the name Kuyper had given to normalist science (Kuyper 1899a, 183; cf. Harinck 2008, 339).

According to VU theologian M.E. Brinkman, Kuitert’s introduction of the evolutionary theory to the Gereformeerden was his most important contribution to Gereformeerde theology; see Brinkman 2024. See also discussion in Kruyswijk 2011, 215–35.

As in the case of the aforementioned examples of the farmer’s knowledge and the case of King Hiram’s woodcarvers in Kuyper’s Eudokia address (Kuyper 1915, 10; trans. Kuyper, section II) the comparison with heathens, Turks, or Peruans on this occasion there evidently is no intention to compliment these gentlemen by comparing them with scientists or medical doctors. The common denominator is the classification of the scientists among mere manual laborers.

The term “materialist” was used to indicate a monistic materialist, someone who denies the existence of a separate, spiritual world.

At that time, Robert Koch was engaged in the search for the bacterial extract tuberculine as a remedy against tuberculosis. Later on, it was disappointingly found to be ineffective as a therapeutic, although still useful for test procedures. For Kuyper, it seems to have been attractive just as “natural” medicine.

For Kuyper’s frequent visits to health resorts, see Snel 2020, 267, 311–12.

The VU, as a private institution, could not afford the financial burden of a faculty of science and, even more so, of a faculty of medicine.

For G. A. Lindeboom, see Van der Meer et al. 1974; Van Bergen 2005, 391–408, 539–558; Van Deursen 2005, 246–48; Van Lieburg 2014.

Elsewhere, Kuyper had referred insanity to the faculty of law (Kuyper 1882, IV and V) and the care of the soul to the faculty of theology (Kuyper 1892, XL). The difference is not quite clear, since Kuyper in the same address used the following phrase: “psychiatry, medicine of the diseases of the soul” (Kuyper 1892, XXXVI).

According to the census of 1899, Rotterdam had almost 20,000 Gereformeerden and Amsterdam around 22,300.

Partial public financing of private hospitals started after the Second World War on a temporary basis only, due to the generally poor financial conditions of the post-war situation; see Juffermans 1982, 122–35, 169–83.

.png)

.png)